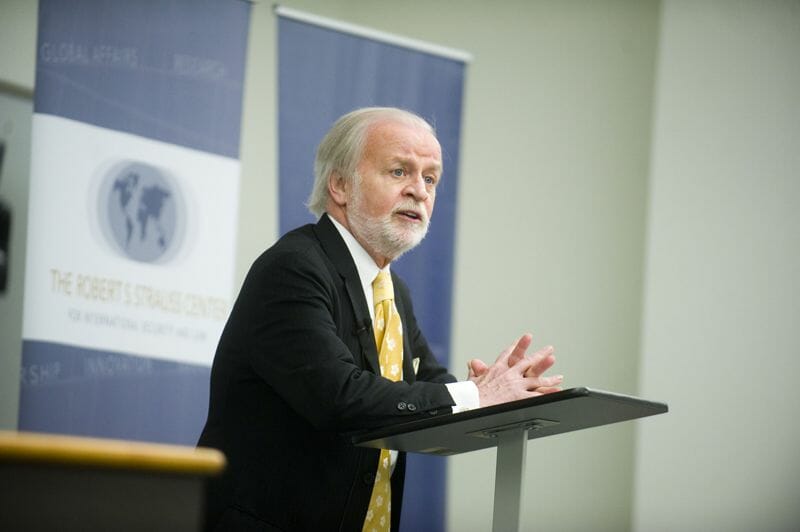

On April 22, 2014, the Robert S. Strauss Center for International Security and Law and the William P. Clements Center for History, Strategy & Statecraft welcomed John Rizzo, Former Acting General Counsel of the CIA, to discuss his recently-published book, Company Man: Thirty Years of Controversy and Crisis in the CIA. The book provides an insider’s perspective on the evolution of the CIA, particularly in a new era of “political” and “open” institutions. The book also aims to shed some light on the types of issues that lawyers enmeshed in the fabric of the Agency have had to face over the past few decades.

Rizzo began his presentation by noting that his life in the CIA was bookended by controversies. In 1975, just before he joined the Agency, he recalled having been fascinated by the “splashy” televised Church Committee hearings. In his own words: “If the CIA did not have any lawyers, they would need some now.” Thus he sent out his résumé, and shortly afterwards, began his 34 year career at the Agency. After 9/11, Rizzo ascended to the position of chief legal officer and became a notorious public figure in the aftermath of the ‘water-boarding tapes’ and enhanced interrogation revelations.

Strauss Center Director Bobby Chesney kicked off the Q&A portion of the talk by commenting on how a large portion of the book is dedicated to the issue of enhanced interrogation techniques. In response, Rizzo highlighted the importance of the context of the 9/11 period in understanding the framework in which his decisions had been made. The CIA and the FBI were severely criticized for not “having done enough” to avoid the attacks. At the time there was also a general belief that another catastrophic terrorist event would happen: a question of when, not if. When the “travel agent” of al-Qaeda (Abu Zubaydah) was caught, interrogators were convinced that Zubaydah knew of the plans for a potential attack. Rizzo explained that had he (Rizzo) stopped the enhanced interrogation program and another attack had in fact occurred, he would have been held responsible. Therefore due to the context of the time and an overwhelming mandate of ‘never again,’ Rizzo gave legal authorization for the program, albeit not enthusiastically.

Although Rizzo knew that this program would “get the CIA in trouble,” during his presentation he acknowledged that back then he did not appreciate the extent to which the “waterboarding” controversy would weigh on the public’s psyche. With regards to the value of the information obtained through enhanced interrogation techniques, Rizzo explained how then and now he thinks these strategies were useful, contrary to what the Senate and the media seem to believe. He said that the Agency would not have engaged in this program for six years, in the face of controversy and scandal, if it was not providing valuable information.

He was also asked his opinion as to why we have seen so many intelligence agency leaks in recent years. Rizzo noted that leaks have always existed in government, but that during the last fifteen years they seem to have increased exponentially. He believes this is due to the post-9/11 intelligence structure, in which more people have access to large amounts of information due to technological changes and interagency sharing of data.

Rizzo ended the presentation by discussing the process of writing and publishing a book on the CIA and topics of national security. Though for the most part his original manuscript remained intact, he was forced to remove certain details. For example, he described how he had to omit the name of a famous Hollywood actor who approached the Agency and offered his help in exchange for cocaine—”which he did not get,” assured Rizzo. Rizzo himself participated in the development of the rules for manuscript publication during his time in the CIA, and thus was aware of what he could and could not address in his book. Overall, he says he is satisfied with the amount of material allowed to be included in the final publication.

For his remarks in full, see below:

John Rizzo had a thirty-four-year career as a lawyer at CIA, culminating with seven years as the Agency’s chief legal officer. In the post-9/11 era, he helped create and implement the full spectrum of aggressive counterterrorist operations against Al Qaeda, including the so-called “enhanced interrogation program” and lethal strikes against the Al Qaeda leadership. Since retiring from the CIA, he has served as senior counsel at a Washington, D.C., law firm and is a visiting scholar at the Hoover Institution. He is a graduate of Brown University and George Washington University Law School.